by Laura Morrison, UOIT STEAM3D Maker Lab Manager

Eager to further study how the use of makerspace tools and pedagogy would impact the learning process for elementary school students, last year our maker lab [STEAM3D, run by Dr. Janette Hughes, Canada Research Chair at UOIT] ran our second-ever March Break Maker Camp.

Eager to further study how the use of makerspace tools and pedagogy would impact the learning process for elementary school students, last year our maker lab [STEAM3D, run by Dr. Janette Hughes, Canada Research Chair at UOIT] ran our second-ever March Break Maker Camp.

Students from the surrounding community attended to learn about math and coding in our “math and coding” morning sessions and about other makerspace and literacy tools in the afternoons. We were specifically curious about how the students would engage with the tools and activities in the camp and what skills, knowledge and competencies they would gain as a result.

The students who attended ranged in age from 10 to 12 (11 boys and five girls). They came into the camp with varying skill levels and backgrounds in terms of comfort with math and their comprehension of coding. As a result, the students learned from each other, the teacher, the UOIT teacher candidates who volunteered during the camp and from the coding program, Scratch, with its embedded tutorials.

The students who attended ranged in age from 10 to 12 (11 boys and five girls). They came into the camp with varying skill levels and backgrounds in terms of comfort with math and their comprehension of coding. As a result, the students learned from each other, the teacher, the UOIT teacher candidates who volunteered during the camp and from the coding program, Scratch, with its embedded tutorials.

First Day

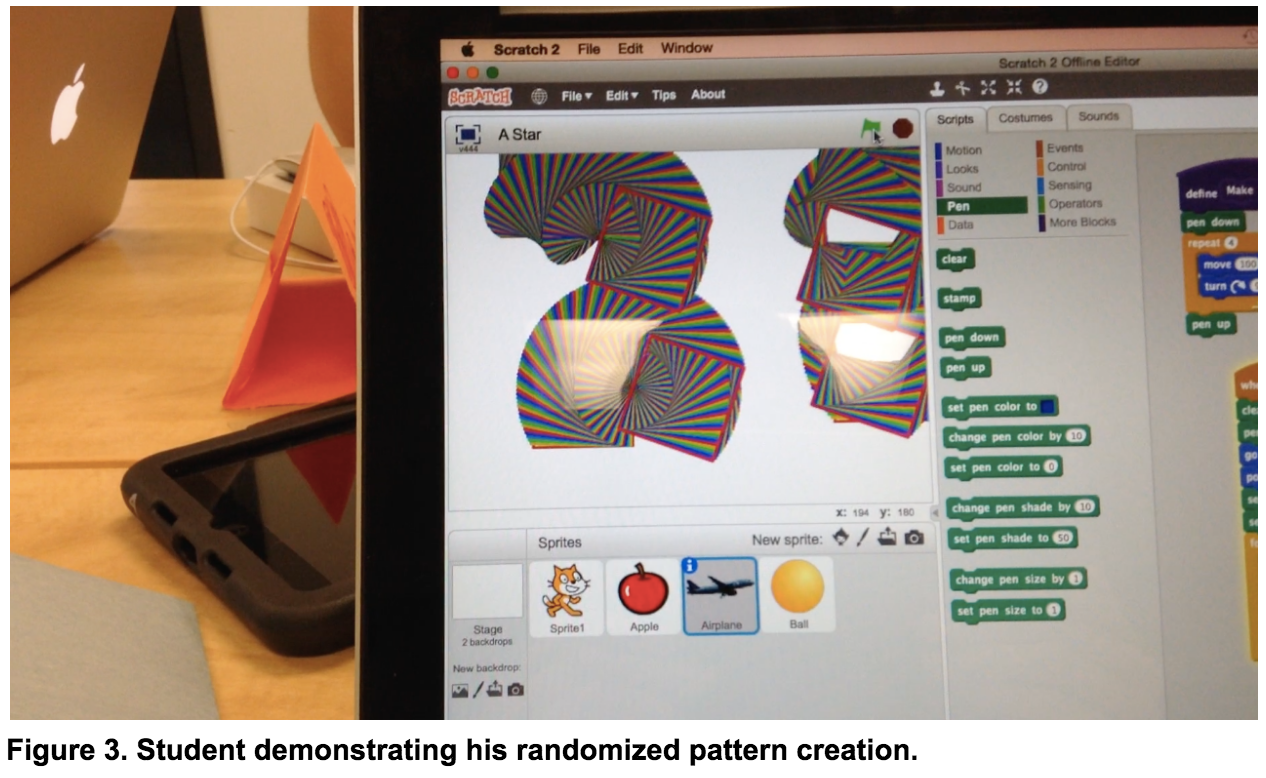

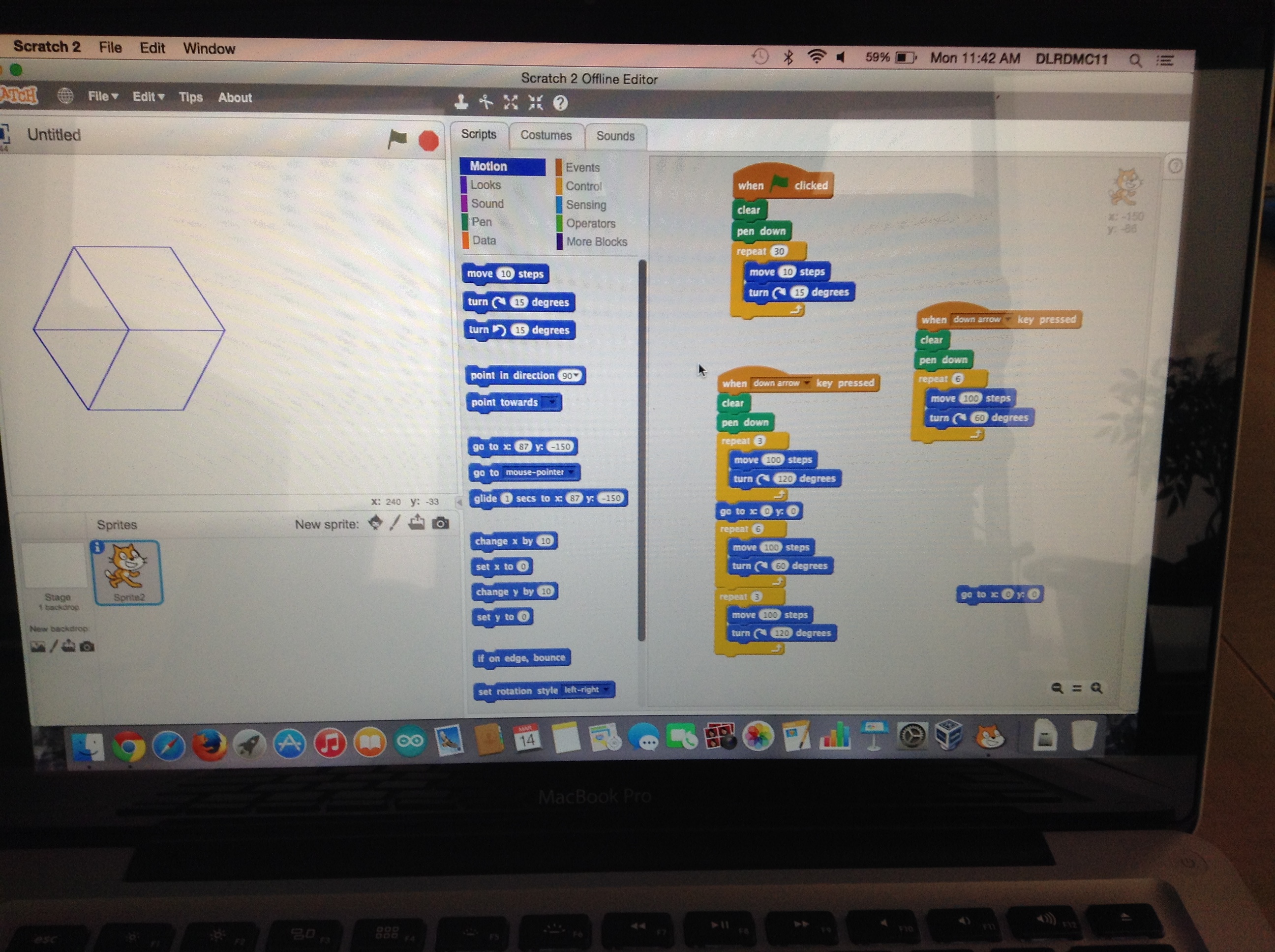

On the first day of the camp, the students were provided with the following prompts as guides to learning Scratch: How do we make shapes; how can we make the shapes move; what kind of art can we make with our code? During this first session, the students answered these mathematical questions using Scratch — inserting commands and values to see what occurred — how their sprite or character moved across a plane.

The art-inclined students were engaged by the colourful and creative shapes that were generated in the program and the math-inclined students appeared absorbed by the speed control the different values added to their sprites. Said one boy of the process: “[I liked] the fact that we got to make all cool designs like a circle, a triangle, a square, and just going [insert rapidly swirling hand motion] and how fast it goes.”

Using pedagogical documentation, we had the students periodically interview one another and record reflections on their experiences. On this first day, in the recordings, many of the students remarked that they were surprised by how easy it was to learn/use coding. In responding to a reflection question about what surprised the students on their first day of the camp, one girl said: “Ok, so, what surprised us today? I thought it’d be really hard, like, all, like, the numbers and stuff, but you’re just dragging and dropping, so it’s a lot easier. We can surprise [our parents] by showing how we can make cool shapes and stuff…cause like the starry things, those are actually pretty cool.”

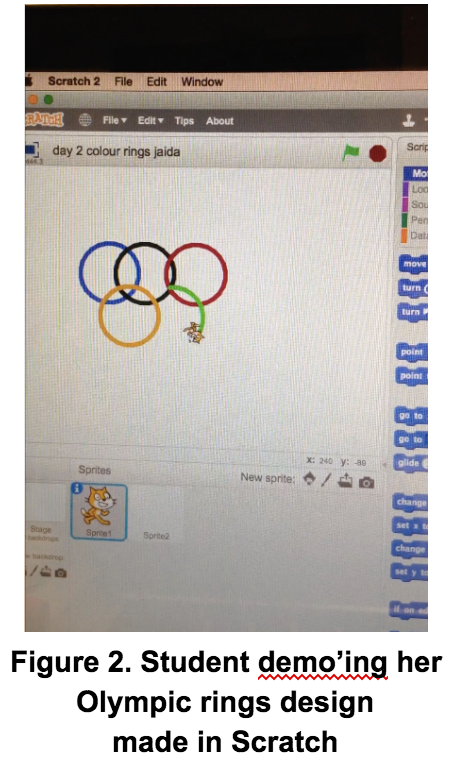

Anot her girl explained in her reflection what she had made in Scratch that morning and all the coding that was involved in a small animation: “That is what happens for Olympic rings. ALL that coding. Yay, so proud!” This was an interesting video clip, as it demonstrated that the students were starting to gain an understanding of the work involved (the depth and breadth of it) in coding even the smallest animations and commands on a computer. It was the beginning of peeling back the curtains of technology and peering inside the box for these students — while also learning mathematical concepts with practical application.

her girl explained in her reflection what she had made in Scratch that morning and all the coding that was involved in a small animation: “That is what happens for Olympic rings. ALL that coding. Yay, so proud!” This was an interesting video clip, as it demonstrated that the students were starting to gain an understanding of the work involved (the depth and breadth of it) in coding even the smallest animations and commands on a computer. It was the beginning of peeling back the curtains of technology and peering inside the box for these students — while also learning mathematical concepts with practical application.

Day Two

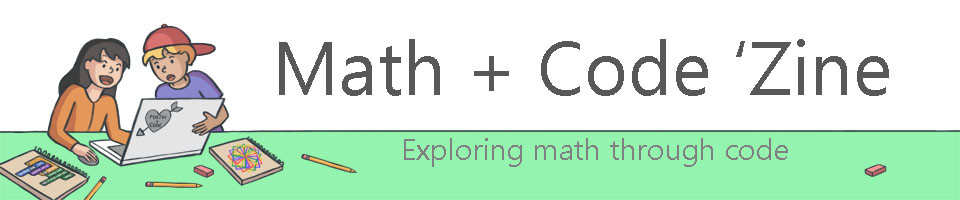

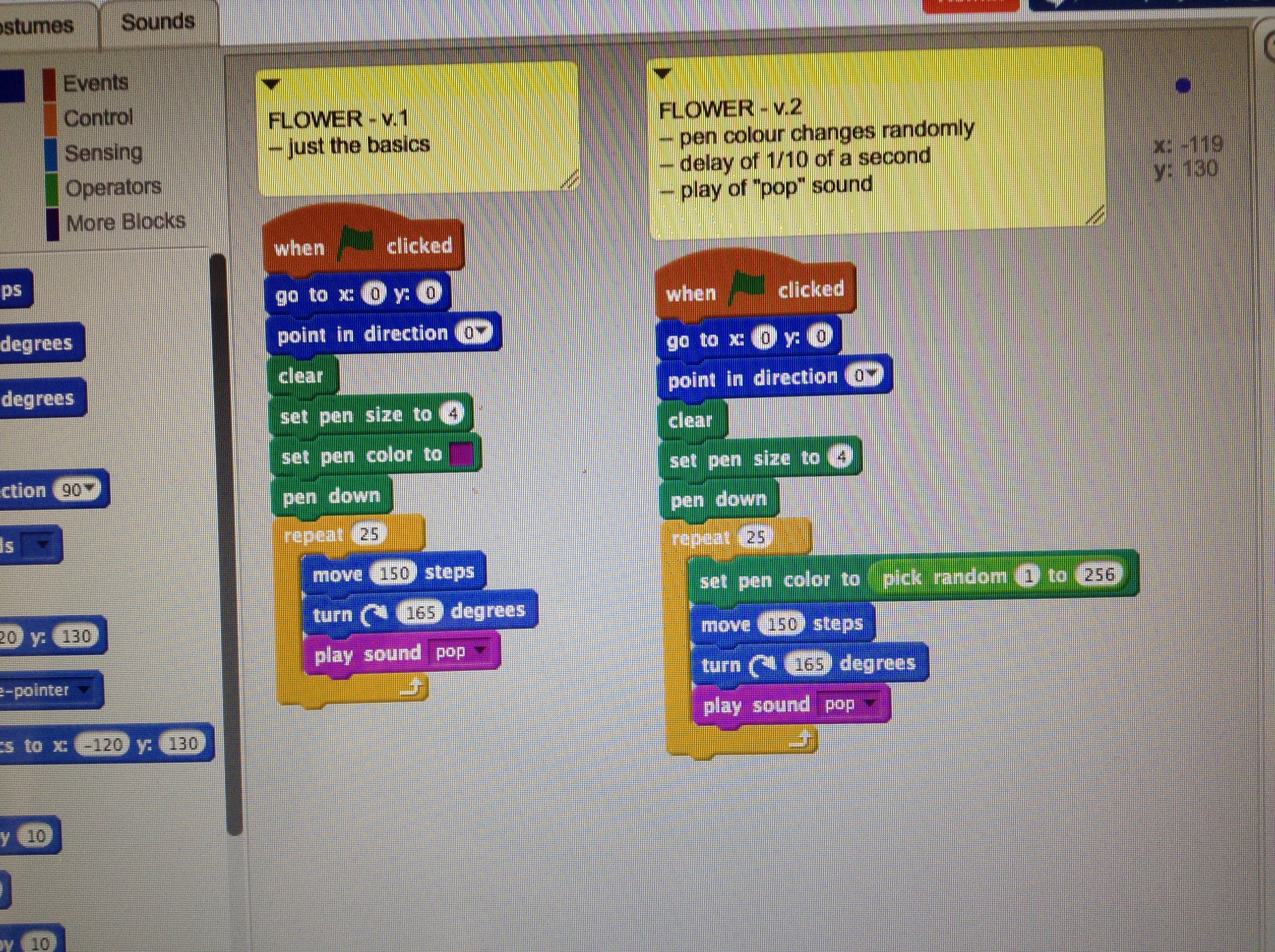

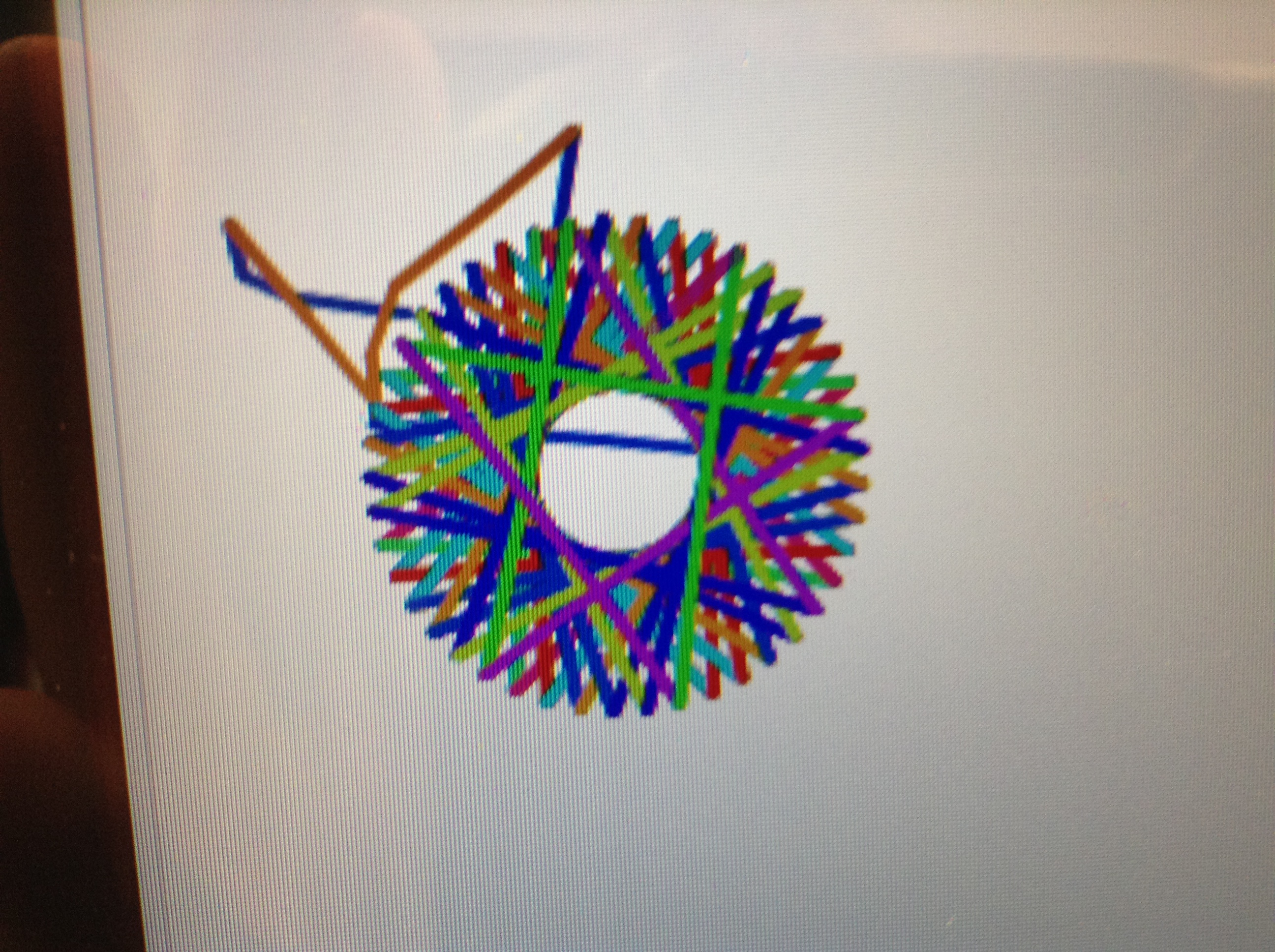

On day two, as the students worked in Scratch, the following math-related questions were posed: What does random mean?; How do we code a random generator?; What different things can we do with random numbers?; What kind of game, simulation or art can we make with our code?

Those students who were captivated by the pattern-generating capabilities of Scratch on day one, loved this session. The marriage of art and math and code in the session appealed to a wide range of student interest and abilities and in a concrete way, demonstrated to the students the relationship between math and art — it was a unique de-silo’ing of subjects that, in reality, should often be referenced together in lessons and instruction.

Sharing their creations with one another was a central component in this lesson — the awe that it inspired in the students and the apparent sense of agency from creating something so interesting in a coding program provided an additional layer of engagement. The students were able to apply mathematical concepts directly in the creation process, which they were then eager to share. The levels of literacy involved in even this simple activity were great. The skills the students acquired in these first days were then applied to more advanced activities and tasks in the final few days of the camp.

Day Three

On day 3, the students had the following guiding questions posed to them: What are our chances and how can we code it? Playing with chance. What are simulations? What kind of game, simulation or art can we make with our code? In this session, the students learned about chance and used this mathematical concept in the coding of either small video games or again, in the creation of simple art pieces. One boy, during a video diary addressed to his parents, shared: “This is what I can do….with the click of a button…see it’s cool. I can do this with the click of a button. Aren’t I cool…I can do that with the click of a button.”

On day 3, the students had the following guiding questions posed to them: What are our chances and how can we code it? Playing with chance. What are simulations? What kind of game, simulation or art can we make with our code? In this session, the students learned about chance and used this mathematical concept in the coding of either small video games or again, in the creation of simple art pieces. One boy, during a video diary addressed to his parents, shared: “This is what I can do….with the click of a button…see it’s cool. I can do this with the click of a button. Aren’t I cool…I can do that with the click of a button.”

Being able to write a fairly complex set of commands and automate a sequence of actions based on the click of just one button was so intriguing to this student, and again, taught another important lesson about technology — the power that learning to code has — the efficiency and productivity one can achieve in understanding how to automate operations that could otherwise be very time consuming. So, not only was this student learning math concepts, but he was also learning skills that could help him achieve greater productivity in his daily life.

Day Four

On the second-last day of the camp, these last questions pertaining to patterns were posed to the students: Patterns, patterns, everywhere… how can we code them? How can we explore patterns in random and determined numbers in code using Python? What kind of game, simulation or art can we make with our code?

About the learning process, one girl shared, “I really liked editing Brian’s game and making it basically, anything I wanted to do with it.” Another boy shared: that he liked, “Being able to change the game that Brian made” and a final student shared, “I liked changing this game to make it better.” This was in reference to the learning scaffolding the teacher had set-up for the students.

As a low-floor entry into the program, the teacher had created a small game and asked the students to review his code and make minor changes to the code in order to personalize it and to become familiar with some of the features. Clearly, making edits to something already established was a easy and engaging entry point for the students and an invaluable piece in the coding learning process.

Last Day

On the final day of the camp, the students were asked to reflect on the general question, how do we perform math & code? They were tasked with preparing some sort of final demonstration piece that could be shared with their parents, summarizing what they had learned about math and code over the course of the week. These were displayed in a gallery walk for the parents, who were amazed by what their children could create. This not only encouraged the students, but also added a new bonding dimension to the learning process — again, creating for greater purpose — for eyes other than the teacher. In an exit interview with one student, one girl exclaimed: “I’m going to get [Scratch] on my dad’s computer. And then I can send you guys videos of my [coded] dance parties.”

On the final day of the camp, the students were asked to reflect on the general question, how do we perform math & code? They were tasked with preparing some sort of final demonstration piece that could be shared with their parents, summarizing what they had learned about math and code over the course of the week. These were displayed in a gallery walk for the parents, who were amazed by what their children could create. This not only encouraged the students, but also added a new bonding dimension to the learning process — again, creating for greater purpose — for eyes other than the teacher. In an exit interview with one student, one girl exclaimed: “I’m going to get [Scratch] on my dad’s computer. And then I can send you guys videos of my [coded] dance parties.”