Julia Houston and Meg Morrison

Originally published November, 2020 at https://juliahouston.wixsite.com/mysite-1

Julia Houston and Meg Morrison are recent graduates of the Faculty of Education at Ontario Tech University.

The versatility of code can be underrated, it works on so many levels (not just math!). This particular blog is dedicated to coding and language, and the possibilities of this partnership, but remember coding doesn’t end there, it lends itself to science, geography, art, and even dance (and pretty much everything else!).

The Inner-Workings: Let’s Get Technical

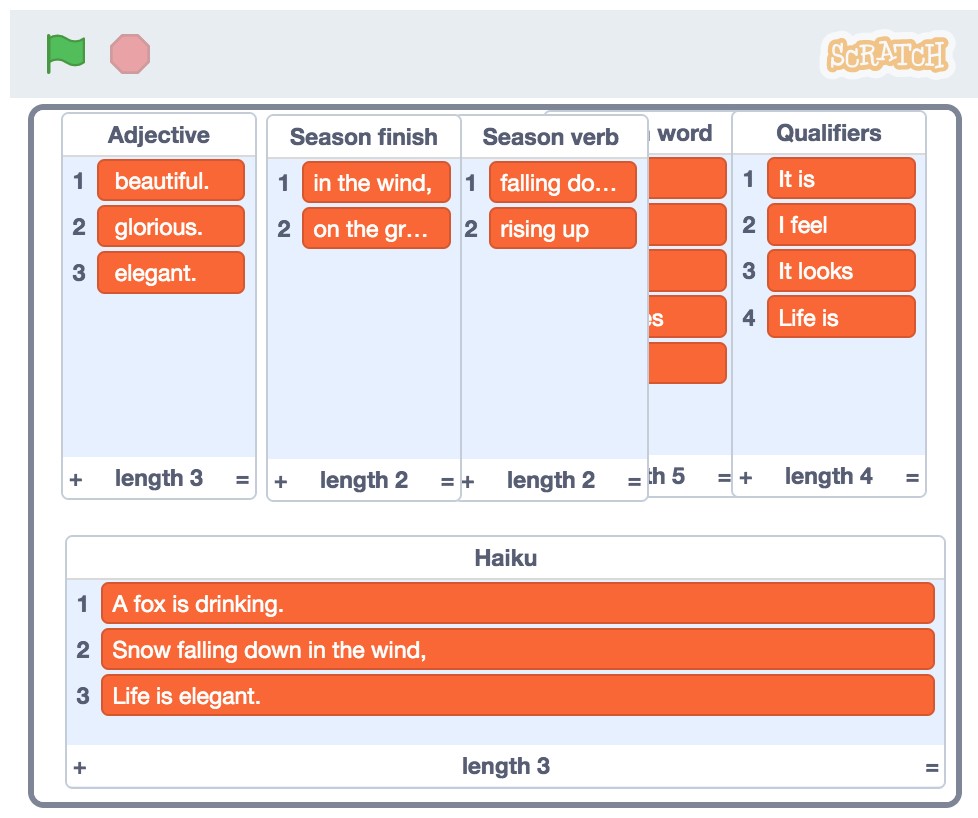

Here, I have inserted a picture of what our code looks like from the inside. Maybe this seems intimidating to you, and maybe it seems simplistic-depending on your background. But, what I do know is, no matter your experience level, I guarantee you can do this.

Go to https://juliahouston.wixsite.com/mysite-1 for a working version of this code

So, let’s break it down. All codes need to start with our green flag block, this is an indication to start running the code, and that’s all there is to it. Now, in order to create a haiku, or any multi-line poem, you’ll need many lists. You can create these under the variables tab. This code involves 8 lists to be exact. I know, it seems long for three lines, but that’s what guarantees the variety of possibilities. The lists are as follows. Animal [contains: A cat, A dog, etc.], Animal Verb [contains: is sitting, is sleeping, etc.], Season word [contains: Snow, Sun, etc.], Season verb [contains: rising up, falling down, etc.], Season finish [contains: In the wind, on the ground, etc.], Qualifiers [contains: Life is, I feel, etc.], and Adjectives [contains: beautiful, glorious, etc.]. All of these lists have been curated so that any combination of qualifiers and adjectives or animal and animal verbs will always equal 5 syllables, as per the first and last lines of a haiku. Any combination of Season word, verb, and finish, will always give us 7 syllables, as per the second line of a haiku. Our Haiku is a list of three lines, so our haiku needs to be programmed in as a list too…now this is our final list! We are almost done creating our moving pieces, before building our code, we create some variables, three to be exact, these variables will comprise our Haiku list, and these variables are line 1, line 2, and line 3. Now, believe it or not, the hard work is done. What’s left is simply to make a code that tells the computer to combine all of these lists together in a way that forms a three line Haiku. The first block that says “delete Haiku” just ensures that the poem starts anew each time, on a blank slate. The second block sets up line one of the Haiku. It states to Set Line 1 to: any random selection from the animal and animal verb lists. These two are connected by a “join” block, so that they appear together in the line. When we add in the block that says “add line 1 to Haiku” we are forming the Haiku list live and from scratch (no pun intended) each time. The next block “say line 1 for five seconds” would have the sprite saying the line in a speech bubble, however, we found this distracting, so we chose to make the sprite invisible (by clicking the eye with the line through it next to the sprite controls) but we kept this block as it pauses the poem building, and lets the user read the lines as they show up. This same logic repeats twice with line two and three, the only difference in line two being the use of two “join” blocks fitted inside one another as the second line has three lists to incorporate. And there we have it, a working, language-based, code!

The Process: Ups and Downs

For this project, we really wanted to create a meaningful connection between coding and language. Initially, we didn’t really know exactly how we were going to make the connection, but after exploring how to visually represent sentences through coding, we decided we would attempt to create a Haiku from codes. We decided to start by breaking down exactly what components we would need to create a haiku. As two people who are discovering the possibilities of coding ourselves, it was definitely an overwhelming start to the project. We essentially began to create the code simply through the trial and error process; guessing what we would need to use, inputting it into our code, seeing why it did or did not work how we wanted it to, and continuing from there. This process definitely took some time, however, collaboration was a huge asset for us during this time. We found being able to navigate coding with a partner really impacted our confidence throughout the process. If one of us felt stuck or frustrated with a certain piece of code, the other would take over and try and solve the issue, and we could talk through our ideas behind why it was or wasn’t working for us. Taking on a task with so many layers within it really showed us the importance of teamwork in coding. Not only are you able to work on the task together, but you are able to hear other people’s ideas, reasoning, and methods behind their codes! This is a great opportunity to build and form new knowledge about coding and the process behind it. While we definitely had a few times where we felt stuck, we found that collaboration and trial and error really allowed us to deepen our understanding of coding to create something really exciting.

Putting This Code in a Lesson

Now, for the fun part: taking this code and turning it into a lesson for your students! We made this code with the intention of being adaptable into many different types of lessons. The most basic way to create a lesson around this code would be as a poetry analysis lesson. Once you’ve created the code with your desired text, you can ask your students to analyse the text to look for specific patterns, words, or themes, and explore the intention behind these ideas (for example, if the class is learning about adjectives, the students could be presented a poem with basic adjectives, and one with stronger, more descriptive adjectives and have the students compare the effectiveness of the adjectives.) A second, more advanced way to incorporate this code into a lesson would be to let students remix the code and create their own haikus. This will let students explore the different parts that make up a haiku, while also allowing them to demonstrate their understanding of adjectives, rhythm, and specific themes. Students will also have the opportunity to explore the code itself and see how the changes they make to the original code impact the haiku. Finally, the most advanced way this code could be used would be to show the students the code and see if they are able to replicate the code themselves through trial and error. This lesson would allow a much deeper exploration of coding as a subject, as well as apply their understanding of haikus, and the components that make up this type of poetry. Overall, this one code can be adapted into lessons of varying complexity, focusing on both aspects of coding and language.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Breaking the barriers of code have nothing to do with breaking the molds of programming, and everything to do with thinking outside of the boxes that we as educators have created in our own minds. Coding was always versatile, we simply decided to see it as mathematical and only mathematical. But, we know this is not true, and that so many possibilities exist for coding in the classroom at any age. In this code, we explored making simple poetry in the form of haikus, but what if we created more complex poetic forms? When we introduce Shakespeare sometimes this rhythm and meter is tricky to master for students. What if they created their own randomized code for iambic pentameter? Breaking down the poetry and seeing it be rebuilt can be a fantastic tool for understanding. With younger age groups, we can use code to look at the properties and usages of verbs, adjectives and nouns through a fun little thing called mad libs! Sure, we can do this without code, but why miss out on the opportunity to teach problem-solving and computational thinking simultaneously with language? What if our students are working on writing short stories, but they’re having a creative block, and they’re stuck for a prompt or their stories have no variety, or maybe, they’d just like a challenge. Imagine a code that randomizes story elements like the 5 Ws (who, what, where, when, and why). Students could receive a unique (and maybe silly) prompt like “A farmer, trying to give his sister a makeover, in space, in the year 200, because the prime minister needed him to”. For younger students using scratch jr. think about storyboarding, or recreating some of their favourite scenes from a picture book the class just read, or to elevate this, recreating the climactic scene (and assessing whether or not students can identify this). These are only a few suggestions to hopefully get the wheels turning, and get you thinking about the possibilities. Happy coding, happy teaching, and happy learning!