By Brendan Roy — Teacher Candidate, Western University

Introduction

This winter I was part of a team of students from the Faculty of Education at Western University who visited a number of different schools in the TVDSB with the objective of introducing both teachers and students to coding. Our target range were students in Grades Four to Eight, thus Scratch was the perfect platform as its block based language is intuitive and easy to use but also allows for countless possibilities.

I’ve used Scratch to make games for students, to create interactive activities and to complement lessons, yet when it came to teaching coding and Scratch, the lesson fundamentals fall back to making shapes. Creating shapes in Scratch is a phenomenal introduction for students with little to no previous background in coding as it focuses on movement creating a very innate exercise in which students are able to imagine themselves putting down the pen and repeating a series of movements and ninety degree turns to create a square. For an introduction, and having tried other approaches, I can’t recommend it enough.

One of the strengths of introducing Scratch through creating shapes is that there are no surprises in the procedure. Regardless of how you look at it, a square is a square and while there are a few different ways a student could create one, the result is the same. Making a circle presents more of a challenge but once again, it’s still a circle. When an end goal is in sight, it’s easier to work towards that. But therein lies the problem, there’s no creativity to the process. For educators looking to fully capture the potential of Scratch however, it’s time to move beyond movement and drawing and take advantage of the more advanced functionality of Scratch.

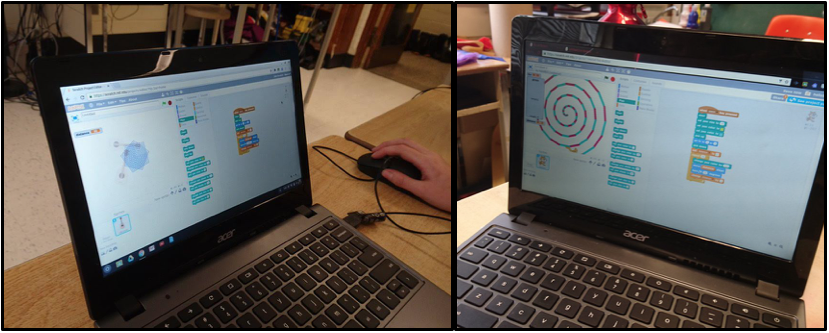

During the project I participated in, I was fortunate enough to be able to spend multiple hours with a Grade Eight Class as I introduced them to coding. We started with shapes but by the end of that first session, a lot of the students were asking for a challenge. To those students, I asked them to create a spiral in scratch. Spirals are tricky because they require the use of variables to create, something I hadn’t taught them yet. The interpretation of what a spiral consists of is also a little more up in the air, as you can see from the following programs created by students in that class.

As demonstrated in the images above, there is a lot of variety in the student creations when they let their creativity run wild. It was at this point that I realized given the opportunity, students are ready for a challenge and when it comes to something they enjoy, they relish the opportunity for something different. Everywhere I’ve been to teach coding, I always get asked “do we get to make video games?” It was something I used to disregard because making video games typically requires a substantial step up and challenge, and is something I thought would be impossible in the time allowed. Yet as I watched these grade 8 students make their spirals, I realized I wasn’t giving them enough credit and thought to myself, why can’t we make video games? So in the next session, that’s exactly what we did.

Variables and Video Games

The lesson I created to teach the grade 8s about building a video game revolved around the use of variables and how they are integral to both scoring the game and storing data for their sprites. The reasoning for this is simple; variables tie nicely into the math curriculum as students from Grades Five to Eight are required to understand variables as part of the patterning and algebra unit. While essential to math, variables are also great because they are an essential skill to computer programming that open up many different, previously unexplored possibilities.

As we progress, I want to highlight some features of the lesson that I taught to this grade eight class. The first thing of note, my strategy for teaching coding is to give students a challenge, give them time to work on it, then as a class, to discuss how the challenge was achieved. So while the scripts I’ve provided are one way of doing what was asked in the challenge, you’ll find your students will come up with different solutions. Don’t discourage these differences but embrace them and see if they work. If they do, your students will be so proud to have thought up of something new and if they don’t, it’s the perfect opportunity to problem solve. Finally, this lesson was completed over three hours. Each component of the lesson fit well into an hour and half block, so it would be easy to spread this lesson out as well.

The complete lesson that you are welcome to follow along with is or use in your own classroom can be found here: https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B_wakMyS_10YT1VSUFJIMzZ4MGM

Basic Game Design

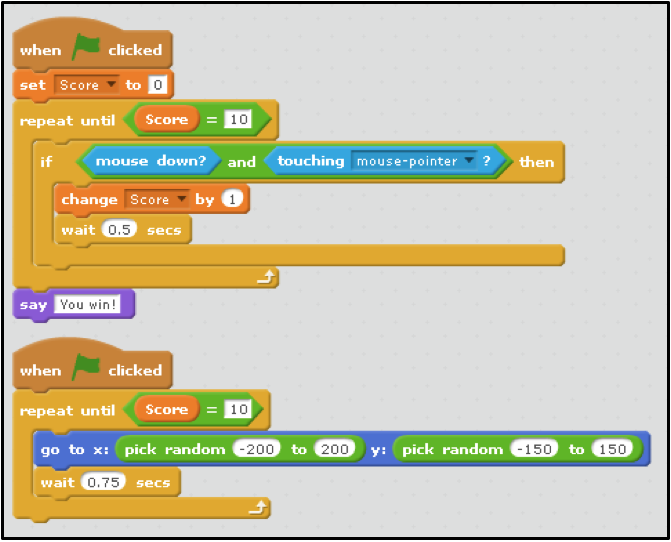

The first component of the lesson saw students create a very simple game that used variables to keep track of the score, with the scoring being achieved by clicking on a Sprite that moved around the screen at random. This consisted of 3 challenges, each of which built off the other, the scaffolding allowing every student to participate while still being tricky enough to make them think. The challenges I used to scaffold the game as well as possible solutions are presented below. As noted previously, these solutions are not the only way of doing it, allow your students to go off the beaten path and try new things.

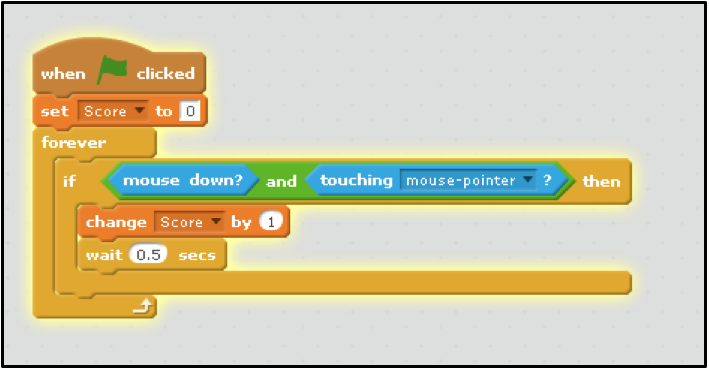

Challenge 1: Every time the Sprite is clicked, change the score by one.

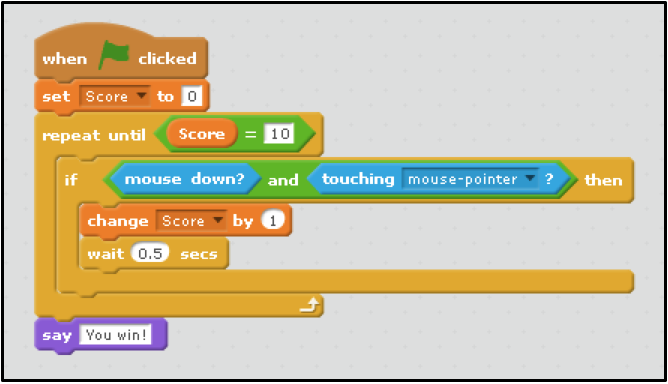

Challenge 2: In your game, pick an endpoint and have the Sprite say “you win” when that score is reached.

Challenge 3: Add some difficulty to the game by making Scratch randomly move around the screen.

After each challenge, I took the opportunity to discuss what students did while going over some key skills such as “if statements”, “sensing”, “repeat until”, “operations”, and “pick random”. This helped focus the lesson while addressing any possible issues. Another helpful tip, and a technique I used, was to put the blocks I used on the smartboard. It was another way to make it more accessible to all students.

Final Product

When completed, the students have a final product in which the Sprite of their choosing moves around the screen at random and the students have to try to catch the Sprite to gain points. A possible sample of the game can be found by searching ‘Roy Basic Game Design’ on Scratch or following the link: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/135826486/

What’s nice about this so called final product is that it’s hardly final. There are still countless options for modifying the game, options I encouraged students to try if they finished early. This included adding a timer, making the game harder or easier, adding multiple Sprites, having the size of the Sprites change as they moved, etc. The point is, encourage your students to be creative and you’ll be amazed as to what they create.

Remixing an Existing Game

The second part of the lesson, and the part that I enjoyed the most, was challenging students to take a pre-existing game, and to make it their own. Prior to the lesson, I created a basic game in which the player defends a castle from villains using a bow and arrow. Students were introduced to the game, allowed to play with it for a bit and then we got to work. The instructions for this were simple and consisted of two parts. First, they had to add scoring to the game. I provided some hints in the script for the program itself but this was all the direction provided. Second was to get creative. Students were encouraged to change the characters and/or the background, add sound, change the speed, change the damage, the number of villains, etc. With a game such as this, there are countless possibilities. While the instructions were simple, every student in that grade 8 class did something different. I saw unicorns firing tacos and dragons spitting fire. It didn’t matter what they did because by making these changes, students need to understand the fundamentals of how the game works. While they are being creative and having fun, the students are still learning about coding and variables.

If you would like to have your students remix the same game, feel free to use the following link (or search ‘Roy Variables and Video Games’ on Scratch): https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/133876842/

Conclusion

While creating shapes in Scratch works as a tremendous introduction to coding, the potential in Scratch extends much further than simply movements and drawings. It’s easy to be tricked by its simple, colourful, block based user interface, but the fact of the matter is that Scratch is a powerful tool with endless possibilities. As an educator, I encourage you to explore these possibilities. While it can be intimidating to explore out of your comfort zone, the nice thing about coding is that problem solving and running into roadblocks is just part of the process. Best of all, as your students explore their creative side through activities such as this one, or countless others, you’ll be learning along with them.